When I first saw this it definitely had the vibe of a Preacher inspired art-hoax, but from what we can tell (including satellite imagery) this is 100% legit. I’d never heard of “earth-art” before the start of this year, but I’m coming to like the ideals behind it, of which one Michael Heizer seems to be the embodiment of.

Heizer’s been working with earth moving equipment to create his large scale-works since the late ’60s, completing a 520 mile “earthwork” in Nevada in 1968 titled Nine Nevada Depressions. A year later he displaced 240,000 tonnes of rock in the Nevada Dessert for a piece titled Double Negative. Apparently this art is something to be experienced, and not in the ridiculous hipster way of experiencing things; this actually sounds pretty cool in context.

Michael Heizer found what he wants to do and has been working at it ever since, also dealing with objects that can fit inside buildings and attached to museums, but reaching the most attention cutting into land and rearranging nature. He hit mainstream headlines again in March when he installed Levitated Mass in to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, having raised $10 million (US) to fund it in the years preceding. All this from a country without a healthcare system. Essentially Levitated Mass is a 350-tonne boulder that sits above a concrete trench that visitors can walk through. Not “experienced” it myself, and certainly could have found a better use for that cash, but the video below on how they moved it 112 miles is worth the 35 seconds it takes to watch it.

There’s loads more videos kicking around on Levitated Mass, including some pretty interesting street shots of the boulder in movement and LACMA sponsored ones explaining it’s relevance (or so they think). Interesting stuff, but the project that’s really grabbed our attention began in 1972, and has been the focus of Heizer’s work since the ’90s. Yep, that’s 40 years in the making thus far.

It’s titled City, and I like to think this is on the lines of what I would do if I won Lotto a few times in a row. People dedicating their lives to building Thunderdome-esque apocalyptic style cities in the middle of the dessert is something we may need more of. The photos of this are just amazing, even to the point of making it difficult to get on the funding high-horse about. Surprisingly, and despite it’s monolithic size, Heizer’s managed to keep it mostly under wraps, and for a long-time no one even knew the location. Even now photos are rough and rare.

Full break down below, from the only site dedicated to Heizer’s work. They’ve hit the nail on the head with this one, not much else to add, collection of photos down the bottom.

via double negative

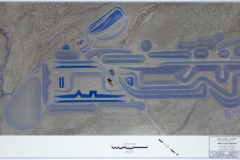

City, Michael Heizer’s life-long project, is quite possibly the largest piece of contemporary art ever attempted. Because the artist is a very private individual, little is known about City, except that he has been working on it since 1972 (he claims 1970). Located in the remote desert of Nevada, City comprises five phases, each consisting of a number of structures referred to as complexes.

Phase One, about which most is known, consists of three complexes. “Complex Two” is the largest complex in the Phase One, and is estimated to reach 70-80 feet in height and a quarter mile in length. The complexes are made mostly of earth, and were inspired in part by Native American traditions of mound-building and the ancient cities of Central and South America. They include massive decorations, such as “stele” on Complex Two, and large, geometrically shaped metal bars on Complex One.

Newly released pictures of a complex in Phase Five of City depict a complicated structure of wedges and shapes named “45º, 90º, 180º” (a name Heizer has used previously for works at The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA and at Rice University, Houston, TX). The form of “45º, 90º, 180º,” like that of “Complex One”, is a play on perspective; when viewed from the front, it appears as one simple shape; only from the side or above does its true complexity come to light. This emphasis on the experience of art from different viewpoints and through time is a recurring theme of Heizer’s work.

The construction of City was originally self-supported, with early funds from gallery-owner Virginia Dwan (who supported his work on Double Negative). Heizer now receives funding from the Dia Art Foundation, through grants (of undisclosed amounts) from the Lannan Foundation, the Riggio family, and the Brown Foundation. With this more stable source of funding, work on City–the total cost of which may run to $25 million–now progresses at a much more rapid pace, and should be completed sometime before 2010.